The problem of the mass line

The first problem is raised by Grexit itself and its relation to the principles of a revolutionary or radical Left party. Stathis Kouvelakis makes a pretty good point in the video “Syriza and socialist strategy” at 43:00-46:00: a party may win an election not on its complete platform, but on one or two basic critical demands of the working class.

No matter what those working class demands are — and if even those demands may be based on conditions that are fundamentally at odds with what the party considers necessary — the party has won on them and not on its complete program.

No matter what those working class demands are — and if even those demands may be based on conditions that are fundamentally at odds with what the party considers necessary — the party has won on them and not on its complete program.

In SYRIZA’s case, the voters wanted an end to austerity, but they do not want to leave the euro, yet SYRIZA is being criticized, essentially, for complying with both these demands: trying to find an end to austerity without leaving the euro. To be clear, the percentage of voters who do not want to leave the euro is twice that who voted for SYRIZA in the election.

(As a sidebar, I should note, of course, in the long run this dispute probably doesn’t really matter, because, the euro is likely doomed in any case — nothing can save the euro from its demise. Even if Greece events don’t trigger the collapse of the euro, France, Spain or Italy will. Now that SYRIZA has won recognition of the humanitarian crisis in Greece, it is only a matter of time before the humanitarian crisis produced by austerity is recognized in Spain as well. And then it is most probably game over for the euro.)

If the conditions imposed on a party conflict with it principles, should the party take power? KKE and ANTARSYA argue that the EU and the euro are imperialist institutions and should be opposed on principle. What does a radical party do when it is elected to form a government, yet its principles are opposed to the opinions of 80% of the populations? Do you, in face of the opinions of 80% of society, declare you will not be bound by this opinion and, having formed a government, promptly go against the dominant position? Or do you refuse to form a government if elected on grounds your priciples contradict the prevailing opinion?

This is a question raised in Stathis’s talk: the radical party is elected for reasons having nothing to do with the program of that party. Assume KKE had been elected: would it then withdraw from the euro despite the desires of the population? Or would it have told the voters: “You elected us, but you disagree with our position on the euro, so we will not form a government.”

Greece voters were looking for a party that would end the austerity. And the voters wanted a party that could do this without leaving the euro. What SYRIZA, KKE and ANTARSYA have in common is that they want to end austerity. Of the three only SYRIZA said, “We will end the austerity without leaving the euro.”

Principles or no, the voters themselves did not want to leave the euro — no radical party can get elected without at least accepting this opinion as the parameters on its scope of action. For the opinion of the population to be consistent with the principles of the radical party, either the principles of the party or the opinions of the working class must change.

Quite simply the objections of the KKE, ANTARSYA, and other radical Left forces are beside the point. The only option open to a party committed to leaving the euro at present is to work within existing working class opinion and hope to move that opinion over time, i.e., the condescending practice of “educating the masses”, wherein the party in question continues maintains it has a lock on truth and the patient education of the masses will, over time, convince them of this.

In any case, no party can form a government to pursue a set of policies that directly contradict the expressed opinion of the majority of the working class — such a thing is not acceptable. Advocates of Grexit must be honest and admit that their gripe is not, in first place, with Alex Tsipras and the SYRIZA majority, but with the voters of Greece, who, by an overwhelming majority, do not want to leave the euro.

The high cost of Plan B

Which brings us to a post by Jerome Roos in ROAR Magazine, which asks whether it is even possible to end austerity within the euro: Ending austerity in Greece: time for plan B?

In the post, Roos makes what is an essentially pragmatic point: No matter what the voters desire, and no matter the principles of the radical party, it may not be possible to end austerity without leaving the euro and the European Union:

“In previous columns, I have repeatedly argued that Germany — as the dominant force inside the Eurozone — would never accept a restructuring of the Greek debt, that the Eurozone would never accommodate a social democratic alternative in its midst, and that as a result Greece’s leftist government would find it impossible to pursue a socially progressive alternative (let alone a radical program) inside the fundamentally regressive, anti-social and anti-democratic straitjacket of the Eurozone.

“These predictions — which are very similar to those made by Costas Lapavitsas and others inside Syriza’s Left Platform — have now been proven correct. Continued Eurozone membership keeps Greece stuck within a web of structural constraints from which it cannot escape without its creditors’ approval. And since these creditors are loathe to set a precedent of successful debtor defiance, they will do anything to prevent Greece from upending the neoliberal austerity doctrine. There can be only one conclusion from this: to truly end austerity, Greece will have to leave the euro.”

Roos assures us the Grexit is not a panacea. It will be painful in the short run without ever actually freeing Greece from dependence on foreign capital or sovereign control of its economy even in the long run. But, he promises, Grexit will allow Greece to establish its own economic priorities along progressive lines.

So, what will be the cost of leaving the euro and do the long term gains for the working class cancel out this cost? Roos explains Grexit is not so easy as simply printing up some currency and replacing all the euros now in circulation in Greece. In fact, Grexit requires the state be prepared beforehand to completely subordinate the whole economy to its control:

“the government would have to be meticulously prepared to manage the extremely difficult transition period, in which the price of imported goods will skyrocket following a sharp devaluation; key commodities like food, petroleum and medicine will have to be rationed to deal with sudden scarcity; capital controls and border controls will have to be reintroduced to prevent catastrophic capital flight; deposits and loan contracts will need to be re-denominated into drachma; and the banks will have to be nationalized to prevent a complete collapse of the financial system.”

So, Grexit may very well mean a collapse of foreign trade, hyperinflation, shortages, rationing of basic goods, and a massive expansion of state power to control its border and the movement of labor, capital and goods?

Really? You want the workers of Greece to mobilize themselves to demand this disaster be inflicted on them? Why would anyone wish this shit on the working class in Greece after it has already suffered five years of austerity?

Roos clearly has no idea of the catastrophe his Plan B would exact on the radical Left across the whole of the eurozone. It is a self-inflicted wound for the Left that is completely avoidable. Moreover, it is a catastrophe that is easy to avoid, with very simple measures within the euro, right now.

Exiting austerity through economic growth

To understand why Grexit is a catastrophe that can and must be avoided, you have to understand what people are attempting to accomplish by leaving the euro. According to some writers, mostly underconsumptionists of various types, SYRIZA cannot end austerity because it does not control its currency. According to this view, the only means to address the problems of unemployment, poverty and inequality is economic growth.

The problem with this view is obvious: In the capitalist mode of production the source of growth in the economy is the production of surplus value. Since this is true, the aim of ‘conventional’ bourgeois fiscal and monetary policy to create economic growth is always and everywhere to increase the production of surplus value.

Simply put, trying to address austerity through economic expansion would place the SYRIZA or any radical government in the position of trying to extract an ever increasing mass of surplus value from the working class. Essentially, the radical government would have to act as the national capitalist.

For the underconsumptionist school, control of the currency makes it possible for the “monetary sovereign” to borrow excess (or superfluous, idle) capital in its own currency. (This capital is excess, superfluous or idle because its owner cannot find a productive use for it, i.e., cannot find a place to profitably invest it.)

Since the state borrows in its own currency and since it can print this currency in any quantity at will, the “monetary sovereign” is held to be virtually immune to default. And since it is borrowing idle capital (which underconsumptionists call ‘excess savings’), rather than taxing it, its access to available capital is not limited to the home country. Thus, the state can borrow superfluous capital from anywhere in the world market and spend it on its food stamp socialism programs.

What underconsumptionists fail to explain (mostly because they don’t even realize it) is that the accumulation of debt turns the state into a mere siphon for stripping off the surplus value of a country. The resulting impact of this on the growth of the economy can be seen, first of all, in the contraction of Greece economy under troika-imposed austerity. As an increasing mass of surplus value is paid out to bond holders, the new surplus value available for expansion of the economy contracts.

Thus, as public debts increase, so also does the steadily growing stream of surplus value to the unproductive holders of public bonds. Whatever short-run gain in terms of economic growth results from the borrowing and unproductively consuming the loaned capital is reversed once the debts have to be repaid.

For underconsumptionists, paying off the public debt is of no concern because the state can always print currency to pay its debts and thus appears to have no limit on the amount of debt it can accumulate. However, in labor theory, how the state pays its debt makes all the difference in the world. Since the state’s debt is always growing, the stream of fictitious profits derived from this debt must be growing as well.

The capital lent to the state is handed over to be unproductively consumed because capital cannot find productive employment for it. This implies the stream of fictitious profits resulting from the debt service have no productive use in the economy as well. The stream of fictitious profits paid out by the state must be lent back to it again and state debt must increase exponentially. While in theory the state can always print to pay its debts, in practice it must always borrow to maintain the illusion of prosperity. The state borrows idle capital (excess savings) to create a false prosperity and its borrows again to service its debt.

In fact, closer inspection will show that it is not the state that determines how must debt it accumulates, but the mode of production that forces its excess capital on the state. Fiscal and monetary policyis driven not by politics, but by the requirements of the capitalist mode of production. For a good explanation of how the mode of production drivesthe accumulation of debt in the public sector and not the other way around, I will let theunderconsumptionist school speak for itself through the writing of Greg Palast, Don’t Lie, It’s Impossible to End Austerity Within the Eurozone:

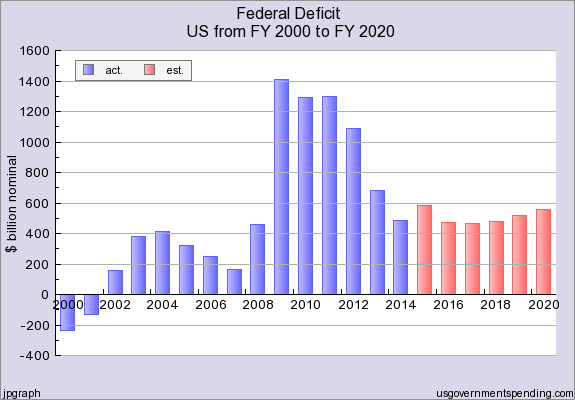

“The United States, to recover from our great recession, went and borrowed 9, 10, 11 percent of gross domestic product. We flooded our economy with $4 trillion in cash through our central bank, and we had over a trillion dollars, way over a trillion dollars, in deficits in a year and a half. It was massive, and that’s how the United States got out of this recession. China went into a massive fiscal deficit and a massive release of funds from its central bank into its system. It’s the only way to survive.”

Palast is entirely correct here that the crisis compelled the fascist state to double its accumulated debt in four or five short years. But he misses a much more important point in this passage: The crisis itself was triggered by an attempt to reduce Washington’s deficits prior to the collapse. In 2004 Washington began to reduce its deficits, which reached its lowest point just prior to the crash in 2007.

So Palast is doubly correct: not only did it take a massive increase in the debt to exit the crisis of 2008, attempts to reduce the budget deficit seem to be correlated with the financial crash itself.

Conclusion

The advocates of Grexit have three big questions to address:

First, are they willing to impose their principles on the working class of Greece, despite the fact every indicator point to an unwillingness on the part of the voters of Greece to consider the Grexit option?

Second, are they willing to embark on a foolhardy attempt to remove Greece from the euro knowing full well that the consequence of this exit would mean an economic catastrophe in the short run with little or no significant benefits over the long run?

Third, is the Left prepared to become the national capitalist in Greece in pursuit of an illusory goal of exiting austerity through an economic growth strategy? Is the Left’s critique of existing society simply that the capitalists are not very good capitalists; that the Left can be a better capitalist: more efficient at extracting surplus value from the working class and consuming this surplus value unproductively?

Grexit is a solution the working class does not want, in pursuit of purely capitalistic goals that the Left does not want.

This is not the alternative you were looking for.

“The crisis itself was triggered by an attempt to reduce Washington’s deficits prior to the collapse.”

Don’t fall for it! I can assure you that when bankers decided to go all ‘Lord of the Flies’ on each other — the actual direct trigger of the collapse — the reasoning wasn’t “Holy shit, have you seen the fiscal stance lately?”

Fiscal deficits/surpluses are largely endogenous. During an expansion, revenues increase and gov spending decreases, all on its own as a result of a growing economy. Now how you grow the economy, and who benefits, matter. But bubbles count, as was the case with the housing crisis and Clinton’s tech bubble. Right up until they don’t, at which point the fiscal stance automatically reverses itself. Rinse/repeat.

Good post, lots to chew on re: Grexit, so I’ll be back. But, for now, POINTS.

LikeLike