Robert Skildelsky, biographer of John Keynes, has written an essay written an essay on the 80 year legacy of the General Theory in which he credits Keynes with inventing macroeconomic policy and for showing  how government could employ means at its disposal to offset economic depressions.

how government could employ means at its disposal to offset economic depressions.

For all the genius of Keynes’ General Theory, its importance has not always been acknowledged by mainstream economics. By the 1980s, according to Skidelsky, most of mainstream economics came to reject many of the ideas first proposed by Keynes, particularly his argument capitalist economies were inherently prone to chronic underutilization of both capital and labor.

Skildelsky attributes the rejection of Keynes policies to three causes: First, Keynesian policies produced a hyperinflationary spiral, which the fascists tried and failed to control by wage and price controls. Second, according to Skidelsky, most economists never really discarded their pre-Keynesian ideas of a self-regulating capitalist market. Third, when Keynesian economic policies ran into hyperinflation, economists like Milton Friedman argued capitalism requires some minimal level of unemployment to control it — an argument that soon won broad following among economists.

“And so the old orthodoxy was reborn. The full-employment target was replaced by an inflation target, and unemployment was left to find its “natural” rate, whatever that was.”

Now, Skidelsky is an acknowledged expert on Keynes, and my opinion isn’t worth crap, but I do want to note two things about this argument that seem wrong to me.

Why is underutilization of capital and labor now chronic?

First, based on Skidelsky’s accounting of Keynes’ General Theory, it is never clear why capitalist economies experienced underutilization of capital and labor during the Great Depression, nor does Skidelsky explain why economies still tend toward underutilization today, eighty years after the depression.

Before the Great Depression economists thought persistent mass unemployment was impossible, yet Skidelsky never actually explains why this changed during and after that depression. Keynes indeed showed why a capitalist economy might have a chronic stubbornly high rate of unemployment, but he did not first do this in the General Theory; rather, in his famous 1930 essay, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, Keynes argued unemployment was persistent because capitalism was doing away with the need for labor. According to Keynes, assuming a constant, steady increase in the productivity of labor over the following century or so, society would eventually be forced to shorten hours of labor.

Thus, behind his General Theory, Keynes made the argument that the emergence of mass unemployment during the Great Depression was a permanent fixture of capitalist economies. Underutilization of capital and labor would increasingly become a widespread problem as the productivity of labor increased.

Now, what no one has ever done is explain why, in 1930, Keynes argued hours of labor would have to be shortened, yet by 1936 he argued government intervention was necessary to prevent depressions not by shortening hours of labor, but by running deficits and maintaining low interest rates. If, as Keynes wrote in 1930, capitalism was reducing the need for labor faster than it could find new uses for labor, by 1936 he was arguing for fascist state economic intervention to find new uses for the labor set free by capital.

The flaw in Keynes General Theory

It is likely, therefore, that the General Theory embodies a serious theoretical flaw: namely, the idea the diminishing need for labor, and the resultant chronic underutilization of both capital and labor, could be overcome by state deficit spending and low interest rates. This flaw might just explain why, by the 1960s, the state attempt to find new uses for labor exploded into borderline hyperinflation: finding new uses for the labor and capital that capitalism no longer needed turned out to be inflationary.

And it might just explain why the solution adopted by capitalist countries to control hyperinflation was sensible. As Skidelsky explains, that solution was simple: just stop trying to maintain so-called “full employment”. In other words, capitalist countries soon discovered that trying to prevent underutilization of capital and labor, even as capitals were shedding labor, was inflationary. So they simply stopped trying to maintain artificially full employment. Not surprising, once government stopped trying to create jobs for workers displaced by rising productivity inflation began to drop.

Skidelsky only gives us half of the story in his essay. In fact Keynes’ General Theory failed because it made no sense in the first place. If the problem was capital’s progressive reduction in the need for labor, it turns out there is nothing state policy can do to counteract this.

This conclusion might have been open to question during the golden age of the 50s and 60s in the middle of the post-war boom, but it hardly needs additional proof today.

Did Reagan bury Keynesianism or praise it

Second, Skidelsky has terribly overstated the extent to which the fascists have moved away from Keynesian policies. To give one example: after the 1970s, which was supposed to have been a period of rejection of Keynesian policies, the fascist state, far from rejecting Keynesian deficit spending and artificially low interest rates, has run a toxic combination of an unbroken string of fiscal deficits and loose monetary policy just as General Theory recommended.

Here is a chart of the debt accumulated by Washington since 1980:

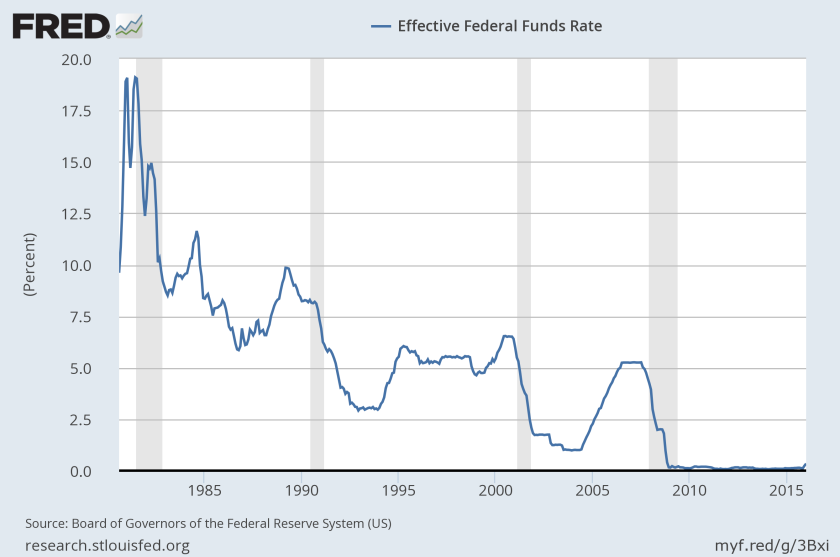

And this how the Federal Reserve have maintained loose monetary policy since 1980:

In fact, the deficits and loose monetary policy did not really begin until the Reagan administration, when Keynes’ theory was supposed to be unpopular. Skidelsky never explains how is happens that Keynesian deficit spending and loose monetary policy becomes routine conditions of the economy only after Keynesian theory has allegedly already fallen into disrepute?

Skidelsky speaks of Reagan as the start of a new neoliberal era, but the plain fact is that continuous deficit and low interest rate stimulus of the sort we have witnessed in the past 35 years was never thought possible before the era of so-called “Reagan neoliberalism”.

Pardon me for saying this, but something about Skidelsky’s argument is very muddled. Rather than neoliberalism signaling the end of Keynesian policies, neoliberalism made Keynesian-style stimulus a permanent and continuous feature of fascist state economic policy. The two most important policy measures prescribed by Keynes to fight depressions — deficit spending and maintenance of low interest rates — are now routine under so-called neoliberalism.

The Reagan administration did not kill Keynesian stimulus policies — it made them permanent.

Thought you’d appreciate this, again:

Grundrisse: “The time a capitalist loses during exchange is as such not a deduction from labour time. He is a capitalist — i.e. representative of capital, personified capital, only by virtue of the fact that he relates to labour as alien labour, and appropriates and posits alien labour for himself. The costs of circulation therefore do not exist in so far as they take away the capitalist’s time. His time is posited as superfluous time: not-labour time, not-value-creating time, although it is capital which realizes the created value. The fact that the worker must work surplus labour time is identical with the fact that the capitalist does not need to work, and his time is thus posited as not-labour time; that he does not work the necessary time, either. The worker must work surplus time in order to be allowed to objectify, to realize the labour time necessary for his reproduction. On the other side, therefore, the capitalist’s necessary labour time is free time, not time required for direct subsistence. Since all free time is time for free development, the capitalist usurps the free time created by the workers for society, i.e. civilization, and capital = civilization. (Page 565-66).”

LikeLike

The move from gold allow the shysters to have it both ways. To divide the classes with scary numbers, while at the same time bleeding the soul of the economy and running it rough and dry to keep their status permanent.

LikeLike

“In other words, capitalist countries soon discovered that trying to prevent underutilization of capital and labor, even as capitals were shedding labor, was inflationary. So they simply stopped trying to maintain artificially full employment. Not surprising, once government stopped trying to create jobs for workers displaced by rising productivity inflation began to drop.”

This is also why UBI is inflationary, right?

I mean, under UBI, the state is giving everyone a basic wage, and some people don’t have actual government jobs, but pretty soon that basic wage is inflated away to spending power of 0.

LikeLike

(1) “To give one example: after the 1970s, which was supposed to have been a period of rejection of Keynesian policies, the fascist state, far from rejecting Keynesian deficit spending and artificially low interest rates, has run a toxic combination of an unbroken string of fiscal deficits and loose monetary policy just as General Theory recommended.”

Rubbish.

Rather, the trend has mostly been budget balancing and refusal to use fiscal policy to increase employment growth.

Don’t you know Clinton ran budget surpluses as did New Labour for some years? That, say, the Liberal government in Australia in the 1990s and 2000s had an obsession with surpluses and paying down debt?

The fact that deficits exist (as in the US in the 2000s) does not mean that the state was using full employment Keynesianism. Rather, the deficits were more cyclical, the results of the business cycle, not actively managed to create full employment.

(2) Also, the 1970s stagflation was not hyperinflation, and had straightforward wage-price spiral and supply side explanations. It was not a demand-side phenomenon.

LikeLike

@Jehu,

Let me first start by saying that your interpretation of Economic Possibilities and The General Theory is interesting and, to me, entirely new. The question you asked (“Why is underutilization of capital and labor now chronic?”) is very pertinent.

Having said that, I believe you are conflating two things: the reduction in hours worked with unemployment.

Keynes believed that wages reflect productivity: for him there was no exploitation. He wasn’t alone in that then, and he is not alone in that now. In Economic Possibilities he was prophesising a happy, rosy future for capitalism: provided it survived, productivity would increase so much that people could afford not working long hours to make a living. Reduction in hours worked, under these circumstances, would be a voluntary decision. He published Economic Possibilities when the Great Depression was just a couple of years old and radical left and right movements were making inroads in Western Europe and North America.

I am sure you’ll recognize in that elements of reformism.

Six years later, the Great Depression was still there. His argument now was that involuntary unemployment was a result of capitalists postponing investment. Capitalists postponed investment because they foresaw low profits, due to lack of consumers’ demand, which was caused by unemployment: a vicious cycle. Government spending (Keynesian stimulus) was the way to break that cycle.

Again, I’m sure you’ll recognise in that elements of the general glut controversy from 19th century political economists.

Now, that would explain why the Great Depression lasted, not why it began in the first place.

For Keynes, who also believed that capitalism was the best possible organisation of society, the only admissible explanation was “animal spirits”. Capitalism wasn’t really failing: people failed. Consumers would get thrifty in excess; capitalists would have panic attacks (I’m not joking: he included among the factors determining investment even the digestion of investors and the weather).

The problem is that if “animal spirits” can cause a depression, then the “confidence fairy” could derail a recovery by Keynesian stimulus: whatever the name, it’s the same mythical beast. If the “animal spirits” are powerful enough to throw an economy into recession once, then they could do it again (Seriously, he even mentioned that the New Deal and a victory of the Labour Party could do just that!)

In fact, austerity could in theory promote “animal spirits”, exactly as “austerians” claim (Again, I’m not joking: even that great among greatest Keynesian economists, Brad DeLong, has admitted that austerity is not an obviously silly policy recommendation).

Bottom line, Keynes has no theory of crisis.

Ultimately, if the problem is that the capitalists’ “animal spirits” are subdued, maybe the best remedy is giving them a mandatory methamphetamine enema.

———-

I am sure you must have heard that most famous of Keynes’ quotes: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir”.

If you think about it, it’s very appropriate that an apocryphal quote makes reference to one of Keynes’ two great talents: his ability to concoct theories and willingness to discard them as frequently as one changes underwear.

After that, his other great talent should result evident: his ability at self-promotion.

My two cents.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comments. Allow me to clarify some parts of my argument you touched on.

First, I don’t think I am confusing unemployment with hours of labor, although my view of that relation may be a bit clouded. For a fuller presentation on the subject, you might want to read my four part series on the relationship between the two that begins here:

https://therealmovement.wordpress.com/2016/04/16/labor-theory-for-marxist-dummies-part-1/

Second, I want to emphasize that I do not think Keynes was a revolutionary theorist. I believe he was just another economist with a particularly good insight into the working of the capitalist mode of production; not unlike Ricardo or Smith. Even when they come to the wrong conclusions, they seem to pose the relevant features in the mode of production in a way not often reproduced by other bourgeois economists of their period. I think it is no surprise that Keynes set out to fix capitalism, rather than kill it; but he does it by starting out with an very good insight into why capitalism was failing; one that cuts to the heart of Marx’s critique: capitalism was reducing the need for labor faster than it could find new uses for labor. This way of stating the problem is at least consistent with Marx’s own argument on the falling rate of profit, and phrased far better than most Marxists today.

The superiority of Keynes argument to the general glut controversy is that he brings the focus to where it should be: labor and labor time. This is decidedly an advance over standard Marxist explanation today that focus on overproduction/underconsumption theories of crises. And even a fair bit more useful than Marxists who focus on the falling rate of profit. Remember, according to Marx, the rate of profit falls because generally less labor is employed in production. Thus, even if the fascists could absorb momentarily gluts by programs like the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933, the quantity of labor time socially necessary for material production would still continue to fall. Chronic excess capital and labor would continue to haunt capitalism.

Finally, I want to say that I find it interesting that, despite claiming to change his mind as facts change, Keynes never let go of his initial verdict that hours of labor had to be reduced eventually. He continued in this vein at least through the war, as shown by his comments here:

http://ecologicalheadstand.blogspot.com/p/long-term-problem-of-full-employment.html

Even 13 years later Keynes in the above notes argues labor time reduction had to begin within 15 years of the end of World War II; i.e., around 1960.

LikeLike

I wish that people would stop whether inadvertently or not over complicating these issues. So many names of old dead people and so many confuscations. So we could sit here our whole lives and misunderstand the issues and misinterpret each other.

It is not a myth that the Reagan administration was the first neoliberal adminstration.

I think your analysis is extremely truncated and hides that in being overly specific. This brings in people who want to confirm their bias that Reagan and the neoliberals are right about economics, monetary policy etc. And offers the facade of legitimacy.

This is the classic neoliberal scapegoat to try blame Keynes, or “the left” without really representing his theories accurately in full context, and then blame the government alone without considering the revolving door that exists from government to banking and finance. Neoliberalism exists on both sides of the aisles left and right conservative (so called) and progressive.

Anyways I am saying who cares about these old economic theories?

Somewhere there is a phD in economics probably not in the US that could accurately and well explain to us all the gory details of history and economics and all the inherent assumptions that are never mentioned. Maybe someone like John Ralston Saul…

But the bottom line is that neoliberalism is a fine and well defined term to explain in simple vernacular why the economy sucks these days on mainstreet. Because the privatization of our public sectors for profit has killed the possibility of sustainable private sector public sector mutualism.

And because they have in the name of free trade and less regulation and freedom and liberty put in place a culture and politics of greed and violence. “Free” and “laissez faire” sounds nice until you realize what it really means- the market does not and cannot self regulate in a way that is net beneficial or just. It’s just like any other system in the known universe- there needs to be rules that are well implemented and designed in order to prevent net detriment. Otherwise we will get the natural outcome which is a dog eat dog world.

LikeLike