There seems to be three major categories of objections to my argument on hours of labor:

First, what material impact will a reduction of hours of labor have on the operation of the capitalist mode of production?

A fall in the rate of profit produced by shorter hours will cause bankruptcies in a lot of marginally profitable industries. The capitalists will not simply respond to a fall in profits by paying workers more. When hours are reduced, the capitalists will unleash an assault on the living standards of workers. Thus, a reduction of hours of labor will lead to an offensive against the social conditions of the working class.

A fall in the rate of profit produced by shorter hours will cause bankruptcies in a lot of marginally profitable industries. The capitalists will not simply respond to a fall in profits by paying workers more. When hours are reduced, the capitalists will unleash an assault on the living standards of workers. Thus, a reduction of hours of labor will lead to an offensive against the social conditions of the working class.

Second, is a reduction of hours of labor incompatible with, or opposed to, the conventional Marxist argument that the working class must seize political power?

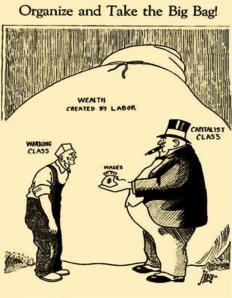

My argument exudes a hostility toward the working class seizing political power. My proposal for reduction of hours of labor treats the capitalist mode of production as an abstraction from the class struggle. Marx insisted that objective economic processes were an expression of class forces. The idea that reduction of hours of labor can lead to communism on its own is economism. Essentially, ending capitalism means abolition of private ownership of the means of production, and the capitalist nation-state system. In isolation from the seizure of state power and nationalization of private property, proposals for changes to the mode of production, like reduction of hours of labor, are reformist.

Third, will the working class itself support a demand for reductions of hours of labor?

Workers believe reducing hours of labor will reduce their income. Hours of labor reduction might result in a shift in such that most workers will actually see their wages fall; although some rise. With a reduction of hours of labor, wages might increase relative to profits, but still fall overall. A reduction of hours under capitalism will only intensify the social crisis of the working class.

***

I’m pretty sure that does not exhaust the list. But they are interesting arguments anyways. Question 3 really is the killer, because if workers think they will be poorer they will never support it. Oddly enough, this was never a problem in France’s 35 hours law. Also average hours of labor in the US right now is about at 34.6 hours per week. Depending on the industry, hours of labor in October varied from 45 hours per week (mining) to 26.2 hours per week (leisure/hospitality). Retail, for instance, regularly runs a work week of less than 32 hours. Most people in the private service sector never see 40 hours per week.

I will probably address these three objections separately in the near future.